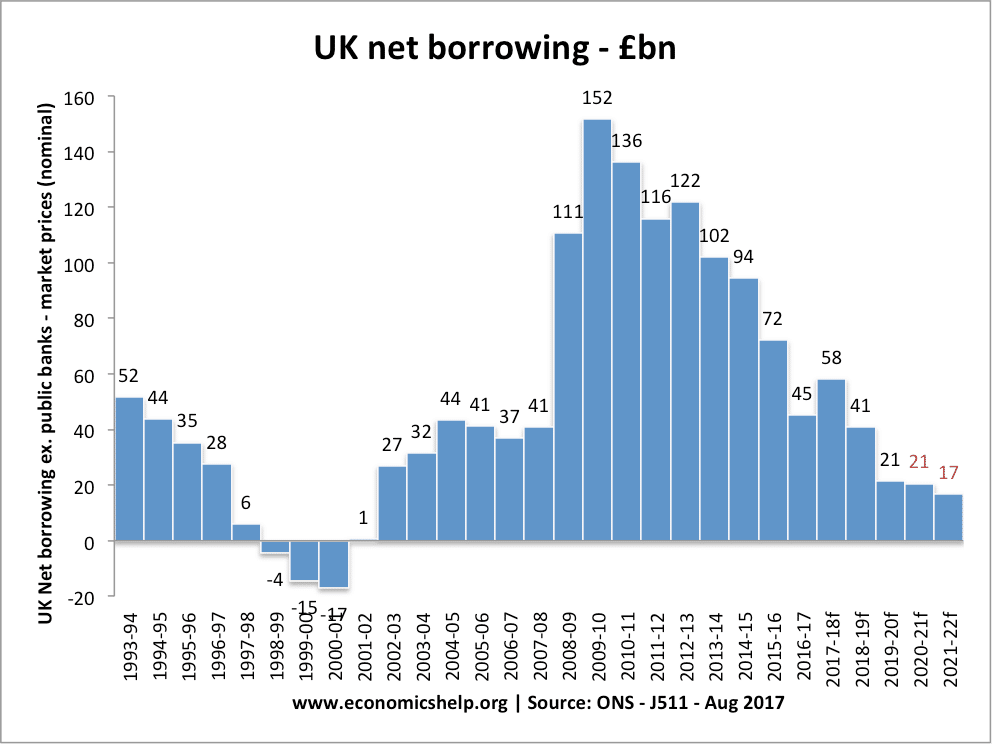

After the economic crisis in 2007-8, the deficit of the United Kingdom skyrocketed to over a record 10% of GDP. In response, a policy of “austerity” was adopted, with an aim to reduce public spending and the government’s budget deficit. This policy has been widely criticised as a Tory ideological attack on the poorest in British society.

However, the mandate to cut the deficit came not from the British government, but from the European Council and Commission. The UK was not the only country which was ordered by the EU to cut public spending – austerity programmes were rolled out by the EU across the whole continent, including in Spain, Portugal, France, Greece and Italy.

To understand how, it is necessary to understand the various parts of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) which allow the EU to dictate the macroeconomic policy of its member states.

The Development of EMU and the Growth of EU Power

In 1993, the Maastricht Treaty was signed, updating the old Treaty of Rome, and further developing Economic and Monetary Union. The Maastricht Treaty was introduced with a view to introducing a single currency, and included “Converence Criteria”, first agreed in 1991, to enable the EU to control the macroeconomic policy of member states.

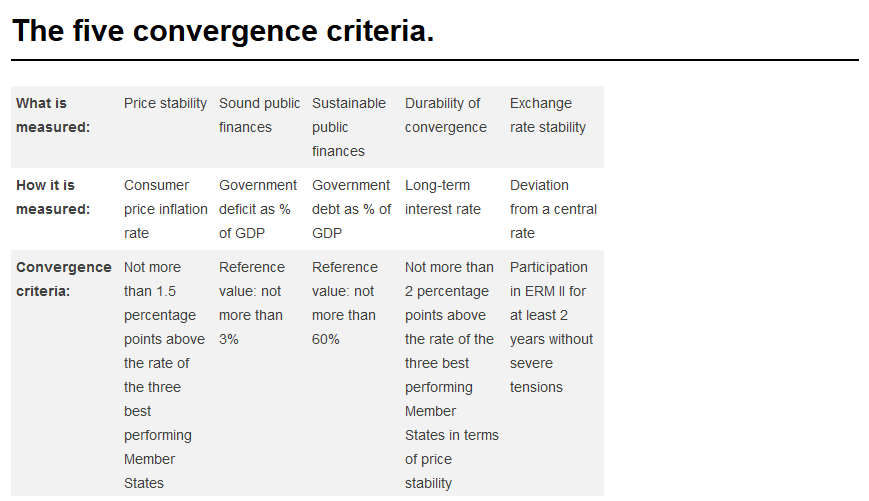

The Convergence Criteria were designed to monitor the spending of member states in order to prepare for the introduction of the Euro. Five convergence criteria were agreed for the member states: “Price stability” (dictating inflation rates), “Sound public finances” (dictating the deficit allowed), “Sustainable public finances” (dictating the level of debt allowed), “Durability of Convergence” (dictating the long term interest rate) and “Exchange rate stability” (dictating deviation from an EU-set interest rate).

From 1993 – 1997, The EU Commission reported on the progress of member states to apply these fiscal measures. The United Kingdom and Denmark secured opt-outs from the Euro, therefore exempting them from annual convergence assessments, however their convergence performance was analysed anyway.

To ensure that the measures in the Maastricht Treaty would be monitored and enforced, the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) was created in 1997. These strengthened measures submitted all member states to fiscal monitoring by the European Council and EU Commission, and the EU also started issuing annual recommendations to member states. All EU member states were automatically signed up to the SGP and by extension, Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). The United Kingdom, despite opting out of the third stage of EMU and the Euro, was included in the scope of the Stability & Growth Pact, and subject to the same measures.

To enforce these rules, a procedure called the Excessive Deficit Procedure was created. If any of the convergence criteria were violated, a process began where the EU set a deadline for the nation state involved to take “corrective action” to bring it back into line with EU rules. The Excessive Deficit Procedure also allowed the EU to take action against Eurozone members for non-compliance, including “punitive proceedings” (including fines). Throughout the late 90s and into the 2000s, the EU strengthened the SGP and the Excessive Deficit Procedure, including the development of new economic governance laws (known as the “Six Pack”), as well as a new “Code of Conduct” for member states.

In 2007, the treaties were consolidated to form the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which is currently in effect. Chapter 1 of the treaty deals with economic policy, and Article 126 details in full the EU’s power over the austerity policy of the member states.

Article 126 states its intent from the first line: “Member States shall avoid excessive government deficits.” The article continues, allowing the EU Commission and Council to monitor the budgetary situation of its member states. It also mandates the Commission to write reports if it believes the deficit of a member state is too high, allows the EU Council to make a decision regarding the member state’s deficit, and issue orders that it be reduced or corrected. Article 126 also allows the EU Council to levy fines on any non-compliant Eurozone member state, as well as advise the European Investment Bank (EIB) to restrict lending.

These are remarkable powers for the EU to hold over its member states. The United Kingdom, as a non-Eurozone member, cannot be fined or be the subject of punitive action, however it is obliged to comply with any recommendations issued by the EU, as a treaty obligation.

The Application of powers to the United Kingdom

The EU has opened Excessive Deficit Procedure measures against the UK three times (1998, 2004 – 2007, and 2008 – 2017) since the Stability & Growth Pact was signed. It was the most recent recommendations from 2008 which led to all major parties in the UK promising to reduce the deficit through austerity measures.

In July 2008, increased spending by the UK’s Labour government and severe economic conditions worldwide led the EU to open a new Excessive Deficit Procedure against the UK. The EU Commission gave the UK six months to “correct” its excessive deficit situation, by cutting its deficit by 0.5% annually as a percentage of its GDP. The UK initially made poor progress, and government borrowing continued to increase throughout 2008 and 2009.

By September 2008, the EU Commission had referred the situation to the EU Council, which also demanded that the UK reduce its deficit. By the following year, The EU Council acknowledged that the UK had not taken any remedial action, and set the UK a deadline of 2015 to end its excessive deficit situation. To achieve this, the EU Council recommended a deficit reduction of 1.75% per year from 2009 to 2015. This was a large figure, not possible through growth of the economy alone. Only by cutting expenditure substantially could this ambitious figure be achieved.

The UK held a general election in 2010, which gave no single party a parliamentary majority. The Conservatives and Liberal Democrats entered government in coalition, promising to urgently address the state of the nation’s finances. By this point, the deficit was running at 10% of GDP, 7% above the EU’s self-proscribed limit, and the government began immediately implementing the EU’s demands for deficit reduction.

It wasn’t until May 2015, after the worst of the financial crisis was over, that the EU Commission assessed the UK’s deficit situation again. Five years of coalition policy had seen the UK’s deficit reduced from 10% to 5.2%. However for the EU, this was not fast enough. The following month, the EU Council published its decision establishing that the UK had been inadequate in its cutting of the deficit, and set a new deadline of 2016/17 for the situation to be remedied.

“…Despite the fiscal consolidation programme set out and being implemented, the UK did not put an end to its excessive deficit by 2014-2015. Furthermore, the UK did not adhere to the average fiscal effort of 1 3/4% which was recommended by the Council on 2 December 2009. Overall, the response by the UK to the Council recommendation under Article 126(7) of the TFEU of 2 December 2009 has not been sufficient.”

— Excerpt from the EU Council’s decision establishing that the UK had failed to take sufficient action to correct its deficit.

In May 2015, there was another UK General Election. Following the demands from the EU Council, the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats all stood on platforms supporting further cuts to public spending in order to “balance the books”, although they disagreed with each other on the extent of them. The Conservatives continued to press the need to “live within our means”, whilst Labour refused to commit to any new spending or additional borrowing. Labour had indeed been trying to pitch EU austerity policy to its voters for at least a couple of years, something which led them being accused of being “Tory-lite”.

“Our starting point for 2015-16 will be that we cannot reverse any cut in day-to-day, current spending unless it is fully funded from cuts elsewhere or extra revenue – not from more borrowing.”

— Ed Milliband, addressing the Labour party conference in Birmingham in 2013.

The Conservative Party took a surprise victory in 2015, and the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, immediately outlined new cuts in the Summer budget, published just after the election. In October 2015 the UK’s Permanent Representative Ambassador to the EU, Ivan Rogers, wrote to Carsten Pillath, Director General and General Secretariat to the EU Council, and Marco Buti, the Director General of Economic and Financial Affairs at the EU Commission, reporting how the budget aimed to fulfill the EU Council’s demands to bring the deficit back below 3%.

The letter detailed how the UK planned to meet the EU Council’s ambitious demands through welfare reform (specifically changes to tax credits and the introduction of Universal Credit), and tax increases, including increasing Insurance Premium Tax, plus clamping down on tax avoidance and evasion. These proposals were accepted by the EU Commission in November. By the end of 2017, the Commission and Council had agreed that the UK had cut its deficit to within its limits, and formally closed the Excessive Deficit Procedure.

Austerity has been a controversial policy in the UK, but there should be no doubt as to where it has come from – the European Union. Although the Conservatives, along with their Liberal Democrat coalition partners, were in charge of implementing the cuts, the instruction to do so very much originated from unelected and unaccountable European institutions, who imposed an austerity ideology upon a whole continent.

This post was originally published by the author on his personal blog: https://joelrwrites.wordpress.com/2019/07/04/austerity-has-not-been-a-tory-choice-but-an-eu-one/

Daily Globe British Values, Global Perspective

Daily Globe British Values, Global Perspective

Well said. Here is a link to a Parliamentary report for the Treasury Committee outlining the UK’s adherence to the Stability and Growth Pact as “good” EU members that also confirms your article:

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmeuleg/301-ix/30113.htm

The EU recommended that the UK cut their deficit. There are many ways of doing this, austerity being only one.

Therefore austerity was NOT forced on the UK by the EU.