Following Boris Johnson becoming Prime Minister in July 2019, Brexiters gained a new impetus and energy to resolve the Brexit deadlock. In response, Remainers in Parliament moved to thwart them, by seeking to take “No Deal” off the table.

They did this on the 4th September 2019, with Hilary Benn presenting the European Union (Withdrawal) (No. 6) Bill (or Benn-Burt Bill) to Parliament. Parliament approved the bill in a matter of days, and the bill received Royal Assent on the 9th September, becoming the European Union (Withdrawal) (No. 2) Act 2019 also known as the Benn Act, or “Surrender Act”.

What does the Benn Act do?

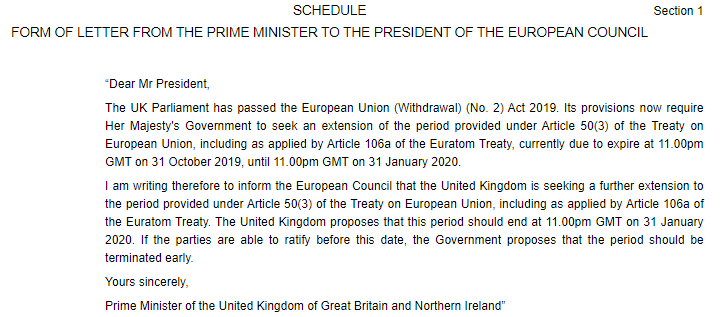

The Benn Act compels the Prime Minister to write a particular letter to the EU, requesting an extension to 31st January 2020. He must send this letter by the 19th October. The letter he must send must be this letter exactly:

The letter that the Prime Minister must send to the EU by the 19th October as demanded by the Benn Act.

The Prime Minister does not have to send the letter if:

- A deal has been agreed between the EU and the UK, and the House of Commons have passed a vote supporting a deal, with the House of Lords debating the issue,

OR

- A government minister initiates a vote in the House of Commons agreeing that the UK will leave with no deal, and the vote passes with a majority.

If the EU refuse the extension request in the Prime Minister’s letter, and make a counter offer (for example a longer extension, or any other extension date), the Prime Minister must accept the offer within two days, unless Parliament holds a vote regarding the new extension date proposed by the EU, and decides not to support it.

The full text of the Benn Act is here.

How can Boris get around the Benn Act?

The government has repeatedly said that it won’t extend Article 50, and that we’ll be leaving on 31st October, deal or no deal. This seems to breach the Benn Act, suggesting that the government may have found a way around it.

There are indeed theories about how the government could get around the Act:

1) Persuade an EU member to veto the letter’s extension request

Whilst the Benn Act says the Prime Minister has to seek an extension, it can’t demand that the EU Council accepts it. The UK can’t veto it’s own extension request (only the EU27 can do this), however it can make it clear that it is firmly against extending Article 50, and threaten to disrupt EU business if the EU27 keep the UK in the EU against the government’s wishes.

The EU Council’s chamber. All 27 other EU member states must agree on an extension to avoid a No Deal Brexit.

Ideas such as threatening to withhold budget payments to the EU, refusing to appoint a Commissioner, or even appointing a hardline Eurosceptic Commissioner (such as Nigel Farage) and vetoing everything, have been floated as ideas in order to make the idea of extension seem unappealing to the EU27.

France made a big issue of granting an extension for Theresa May, so could be tempted to exercise its veto. A more eurosceptic government like Hungary could also be persuaded to veto. However whilst the UK remains a massive budget contributor, and whilst Remainers have a majority in the House of Commons, the EU are likely to favour extending the process to try and encourage a second referendum.

2) Get a Deal

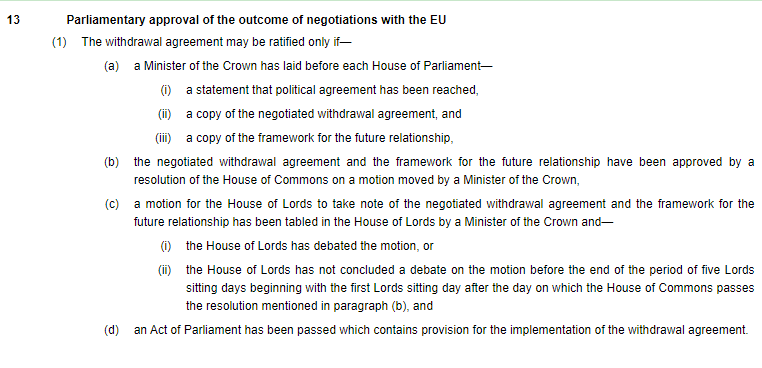

The Benn Act states that the Prime Minister does not have to send an extension request if the EU and UK conclude a Withdrawal Agreement.

The UK would then leave the EU as soon as that deal is agreed by both the British and European Parliaments, assuming any other associated legislation was passed in time.

The government is working to do this, but the chances are that a deal is agreed and ratified, as well as being passed by the House of Commons and the European Parliament currently looks slim. Any arrangement that is acceptable to the House of Commons is likely to be rejected by the EU, and any arrangement proposed by the EU is likely to be rejected by the House of Commons. The two sides appear far away from agreement, and there is significant time pressure.

3) Get a deal, but refuse to introduce legislation

The Benn Act’s requirement to write a letter requesting an extension to Article 50 simply falls away if the UK Parliament passes a vote saying that it approves of a Withdrawal Agreement that is brought before it.

Therefore, Boris could bring a deal that has been agreed with the EU to Parliament before the 19th October, and pass it through Parliament. However one additional thing needs to be done to avoid no deal. An Act needs to be created and passed through the House of Commons to make the Withdrawal Agreement law, and it needs to be done by the 31st October.

Boris’ government could refuse to introduce this legislation needed to make the Withdrawal Agreement law (or even vote against it), after first passing a motion regarding the Withdrawal Agreement. The passing of the motion would mean an extension doesn’t need to be requested, and the lack of legislation writing the Withdrawal Agreement into law would mean the UK drops out of the EU without a deal on the 31st October.

This option would require Boris to say to the ERG and the DUP in private: “vote through this deal in Parliament, and No Deal will happen.” The opposition would likely suspect a trap, and it may be difficult to pass the initial motion through the house without a guarantee that the following legislation would also pass. Some rebel Labour MPs would be required for this strategy to work.

This flaw in the Benn Act was pointed out by Remainer barrister Jolyon Maugham here.

4) Refuse to amend the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018

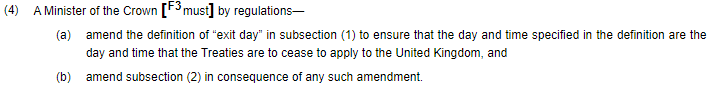

When Theresa May extended Article 50 last time (from the original date of 29th March to 31st October) she needed to amend the “Exit Day” defined in the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, in order to make British legislation match with EU law. May did this by passing a statutory instrument through the House of Commons on 27th March, which was unsuccessfully challenged by Robin Tilbrook of the English Democrats.

Section 20(4) of the Withdrawal Act 2018 says that if the EU and the UK agree an extension, the definition of “Exit Day” must be amended.

Boris Johnson could hypothetically comply with the Benn Act, securing an extension to Article 50, but then refuse to amend British law. There would then be a conflict of legislation.

EU law is supreme over UK law via the Precedence Principle. However the jurisdiction of EU law in the UK is only made possible by the European Communities Act 1972, and this gets automatically repealed on “Exit Day” (and the commencement order for repealing this Act has already been signed). If Boris Johnson refuses to amend the “Exit Day” in the Withdrawal Act 2018, then the European Communities Act 1972 is repealed on 31st October, and the UK could fall out of the EU without a deal.

Brexit Secretary Stephen Barclay signs a “commencement order” to trigger the end of the supremacy of EU law in the UK from the 31st October.

However it is unclear, with the enacting of the Withdrawal Act and the repealing of the European Communities Act, whether Article 50 would still apply to the UK and take precedence over UK legislation.

This inconsistency was raised by Bill Cash MP in the House of Commons on the 26th September 2019. It’s expected that court action by Remainers could force Boris Johnson to amend legislation to avoid us dropping out, or it could be ruled that this legal inconsistency does not stop us being part of the EU and bound by Article 50.

5) Write a second letter

This is related to point 1). It is argued that the Prime Minister could send the letter as ordered to by the Benn Act, and then send another letter nullifying it sometime afterwards.

It’s uncertain which letter would take precedence, and a court could rule this option as unlawful. But if the EU accept the second letter as overriding the first, and a court fails to act in time, then the UK would leave the EU without a deal.

6) Ignore the law

Remainers currently in the courts fear that Boris could simply refuse to send the letter, or send it and refuse to accept any counter offer made by the EU.

The courts would likely act quickly to enforce the law in this scenario, either by sanctioning Boris personally (including threat of arrest), or by bypassing him and finding someone else to send the letter.

Boris could also resign on the eve of having to send the extension request letter, but it would be likely that the Civil Service or other Minister would be required to send it. This option is unlikely as the government have committed to following the law.

The following options are a bit more outlandish, but have featured in the media as possible options:

7) Invoke the Civil Contingencies Act 2004

The Civil Contingencies Act alows the government to announce a state of emergency, and amend legislation (apart from the Human Rights Act) if there is imminent threat to the nation. Some Remainer MPs, including Dominic Grieve, have theorised that the government could use the cover of potential Brexit inspired riots to invoke the Civil Contingencies Act, disapply the Benn Act, and then leave the EU with no deal on the 31st October.

The problem with this is that the Civil Contingencies Act states very clearly what is considered a “national emergency”. It is unlikely that the government would be able to meet the grounds for a “national emergency” as stated by the Act without being challenged and overruled by the courts.

8) Use an Order of Council

In September 2019, John Major suggested that the government could use an ‘Order of Council’ to circumvent the Benn Act.

An Order of Council is a prerogative power issued by the Privy Council (government ministers), which could in theory be used to amend legislation. Approval from the Monarch is not required.

Orders of Council are more commonly used to amend things like the bylaws of a chartered institution. Using it to change primary legislation would be unprecedented, and would likely be challenged in the courts under a breach of parliamentary sovereignty and the Bill of Rights 1688.

The government itself has dismissed the idea of using an Order of Council to disapply the Benn Act.

There are potentially many ways in which the government could work around the Benn Act to ensure we leave the EU on the 31st October, with or without a deal. However many of them are uncertain to actually work, and some after legal clarification may not be viable loopholes at all.

On the other hand, there may be loopholes that the government have found that have not been made public.

This post was originally published by the author on his personal blog: https://joelrwrites.wordpress.com/2019/10/11/how-boris-can-get-around-the-benn-act/

Daily Globe British Values, Global Perspective

Daily Globe British Values, Global Perspective