Following Britain’s momentous vote in 2016 to leave the European Union, an international organisation has hit headlines numerous times, and was key in the campaigns during the referendum: The Commonwealth of Nations, commonly shorted to ‘The Commonwealth’.

After the UK joined the EEC in 1973, the importance of the Commonwealth and Commonwealth related issues and projects had taken less importance in British foreign policy and suffered correspondingly in the public eye. The UK’s attention focused mainly on the North Atlantic and European areas, somewhat at the expense of global ties. It was, however, probably the most global of the EU nations, but reaching new bilateral trade deals are difficult enough with two parties; when there are 29 the time it takes to reach agreements with nations while inside the EU is readily understandable.

Post-Brexit, this has created a situation in which the UK is isolated and cut off from what was the cornerstone of its foreign policy – the EU. Relatively alone in the world, many have proposed the Commonwealth as a solution to the UK needing to join a national block. They see an increasingly polarised world with increasing geo-political issues and tensions, and point to the numerous good reasons for greater Commonwealth ties.

However, after numerous decades of not having a major role in British foreign and domestic policies, the British public have many questions about the Intergovernmental Organisation (IGO). They include: “What is the Commonwealth?”, “Does it have a future?”, “Has Brexit made it weaker or stronger?”, “Do the other member-nations like the UK?”, “Isn’t it just an ex-colonial Club designed to serve as an opiate to imperialistic geriatrics who harken back to the ‘Golden Days’ of the British Empire?”

Many of these questions and others related to the Commonwealth are very common. Their variety and regularity reflect a regrettable lack of understanding about the Commonwealth, its history and how it works. As it has been a key to British foreign policy directly for about 90 years and indirectly for many years before that, it is a shame that it has slipped out of national thought.

Therefore, in this series, we will be examining the Commonwealth of Nations, its history, aims, organisation and operations. We will also consider the many ideas, blocs, associations and concepts that have originated from the Commonwealth, from their beginning in the 18th Century to the present day.

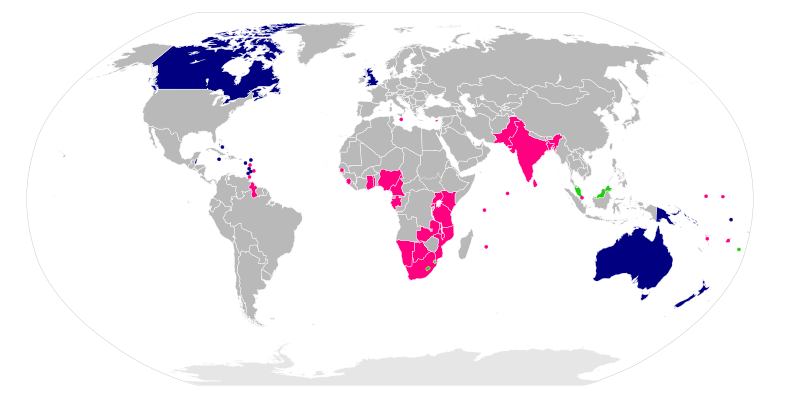

Blue = Realms, Pink = Republics and Green = Other Monarchies

The Commonwealth of Nations:

The Commonwealth of Nations is best described as a club for nation-states. As a diverse collection of 52 member-states, it exists as an unusual association spanning all continents. It is international and intergovernmental, yet not supranational, meaning members do not lose their sovereignty. Although Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II is the Head of the Commonwealth, in the majority of nations she has no other role and the position carries little real authority. Membership has few requirements (especially when compared to the EU), no large payments, and it cannot be compared with political, economic or defensive pacts.

Its main emphases are on Human Rights and Sustainable Development; noble and relatively uncontroversial topics. Some have defined it as a smaller UN to whom nations pay attention when it speaks on the few issues within its remit. While this is a somewhat cynical definition of the UN, it is important to recall that the Commonwealth has had a more successful history in restoring representative government and human rights in their member states than the UN has.

The best way to describe it is probably as a ‘club’ in which each member has an equal say. A traditional definition was that it was a “Round Table”, referring to the myth of King Arthur and the knights who all met as equals. Despite common assumptions, it is not an association merely for ex-British colonies, protectorates and mandates, as a number of such nations have not applied for membership, and two nations with no British Colonial history are Commonwealth Members.

The members of the Commonwealth are:

| Antigua and Barbuda | Australia | Bahamas, The | Bangladesh |

| Barbados | Belize | Botswana | Brunei Darussalam |

| Cameroon | Canada | Cyprus | Dominica |

| Fiji | Ghana | Grenada | Guyana |

| India | Jamaica | Kenya | Kiribati |

| Lesotho | Malawi | Malaysia | Malta |

| Mauritius | Mozambique | Namibia | Nauru |

| New Zealand | Nigeria | Pakistan | Papua New Guinea |

| Rwanda | Saint Christopher and Nevis | Saint Lucia | Saint Vincent and the Grenadines |

| Samoa | Seychelles | Sierra Leone | Singapore |

| Solomon Islands | South Africa | Sri Lanka | Swaziland |

| Tanzania, United Republic Of | Tonga | Trinidad and Tobago | Tuvalu |

| Uganda | United Kingdom | Vanuatu | Zambia |

On February 13, 2017, Boris Johnson announced that The Gambia announced they too will be re-joining the Commonwealth, becoming the 53rd member.

History:

The Commonwealth (not to be mistaken for the English and British Commonwealths of the 1600s) was founded in 1931 when the British Parliament passed the Statute of Westminster. This gave the dominions of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa and Eire (now Ireland) de-facto independence and ended colonial control. As the process of decolonisation continued, they continued to share most law, customs, the English language and the Crown. During this period, it was known as the ‘British Commonwealth’, reflecting its growth from the British Empire.

However, in 1949, when the Commonwealth Prime Ministers met in London for their conference, a profound change in the Commonwealth ensured, and a new type membership was created. India had gained full independence in 1948, and while they wished to remain a member of the British Commonwealth, they were transitioning to a Republican form of government. For some, including South African statesman and general Jan Smuts, this was shocking. An inherent part of Commonwealth membership since its foundation in 1931 was that all shared the same head of state, who at that time was King George VI. This was enshrined as the primary reason for the existence and purpose of the British Commonwealth according to the Statute of Westminster, which assists in understanding the level of opposition to such a proposal.

A solution to the crisis was found in the creation of the post of ‘Head of the Commonwealth’, which would be held by King George VI, and the changing of the name from the ‘British Commonwealth’ to the ‘Commonwealth of Nations’.

The London Declaration of 1949 proved to be pivotal, and led to the expanse of the Commonwealth following decolonialisation. Today only sixteen members of the Commonwealth share the same Head of State, HM Queen Elizabeth II (or Elizabeth the First depending on nation) and are known as Commonwealth Realms. Five have their own monarchs, while the thirty three other members are all republics. This freedom to choose the type of representative government is an example of the inherent flexibility and survivability of the Commonwealth and both qualities are closely related.

Indeed, in a development that few delegates at the London conference would have imagined, the two most recent members (Rwanda – 2009 and Mozambique – 1997) of the Commonwealth have no historical attachments to the British Empire, having been part of the Belgian and Portuguese Empires respectively.

However, the Commonwealth has not been an unalloyed success. Ireland, Zimbabwe, and the Maldives have left, while Pakistan has been in and out, including numerous suspensions. Other nations have felt no need to join the Commonwealth following independence; such nations are located mainly in the Middle East, and Jordan, Israel and the Gulf States spring to mind.

By http://www.thecommonwealth.org/, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41649835

Purpose & Goals:

The Commonwealth has a number of primary goals, the main being the upholding of democracy, human rights and the rule of law. Following this is the aim of sustainable development to ensure better living standards for the citizens of all member states. To achieve these ends, it is guided by the Commonwealth Charter, which contains 16 articles outlining freedoms and equalities. These are:

| 1. Democracy | 2. Human Rights | 3. International Peace & Security | 4. Tolerance, Respect and Understanding |

| 5. Freedom of Expression | 6. Separation of Powers | 7. Rule of Law | 8. Good Governance |

| 9. Good Governance | 10. Protecting the Environment | 11. Access to Health, Education, Food and Shelter | 12. Gender Equality |

| 13. Importance of Young People in the Commonwealth | 14. Recognition of the Needs of Small States | 15. Recognition of the Needs of Vunerable States | 16. The Role of Civil Society |

Membership:

The Commonwealth is a voluntary association. As such, nations are free to leave or request admittance. A number of conventions and agreements state the requirements for entry, and the most recent exit was in 2016, when the Maldives left. The reason for their exit was the pressure placed upon them about their undemocratic and nontransparent government by the Commonwealth.

A few nations have had their membership suspended, but while the organisation can eject members it has not done so. Suspensions have typically been because of lack of transparency, human rights and democracy. However, it has not been purely punitive, and when corrective measures are performed by the nation, it is eagerly accepted back into the family. An excellent example of this would be South Africa, which left upon becoming a republic but re-entered the Commonwealth following the end of Apartheid (1994). Fiji is another example; following the end of military control in the 2014 democratic elections in the republic, it has been re-instated as an equal member.

The two most recent applications for membership are both from African nations; South Sudan and The Gambia. In South Sudan, the application was lodged soon after independence, but little has been heard since.

Following the democratic presidential elections in Gambia, Adama Barow, the victor, has stated his desire to re-join the Commonwealth, which has been welcomed by the Commonwealth Secretariat. Of note is that The Gambia exited the Commonwealth in 2013 after pressure against the human rights violations of the Jammeh Regime. President Jammeh, who seized power in a military coup, became infamous for stating that he could cure AIDS with bananas and that he could rule for a billion years, yet was forced to step aside last year.

Therefore, most nations that leave the Commonwealth do so because they do not accept the importance of human rights, democracy and tolerance – the famous “British Values”. Despite many accusations of neo-colonialism from the nations which leave, it would appear that they are merely continuing the old tradition of dictatorships venting public frustration internationally. For that reason, there is little risk of unbiased reporters or citizens viewing the Commonwealth as a neo-colonialist institution.

For any potential intra-Commonwealth association, this is an important foundation to build on; there are a number of things any future Commonwealth treaty must be very wary of, and neo-colonialism is one of them.

Despite this apparent laxity of the requirements for Commonwealth Members, there have been quite a number of agreements on methods of accession since the London Declaration, which will be mentioned in greater detail in subsequent articles.

Heritage:

Commonwealth nations typically have a lot in common – Common, or hybrid Common Law system, the English language in various forms, similar forms of government, similar emphasis on human rights and due process of law. As such it has been noted numerous times that it is easier to conduct trade with nations with similar cultures, law and language, and this is the greatest benefit of the Commonwealth to Businesses. The Commonwealth Exchange, a London based Think-Tank, has published an excellent set of pamphlets about UK-Commonwealth trade.

It would be remarkably hard to over-emphasise the importance of the common heritage, which in many cases is actual family ties; six out of ten Britons have family members who live in a Commonwealth nation. It is clearly the strongest connector and it enables over fifty nations from all the continents (if we include the Sub-Antarctic Islands and Territorial Claims as Antarctica) to meet and work together. It is in most part due to this common heritage, that any proposals for closer integration can be considered without the spectre of the British Empire and also the EU hanging over the national heads like the Sword of Damocles. It can be argued that the common heritage enables any Commonwealth association to have a considerably higher probability of long-term stability than any other association. Whatever proposals are considered later, all must harness this remarkably flexible strength to ensure it offers the most benefit for all citizens of all the nations involved.

Why Closer Ties

People may wonder why the proposals to concentrate or focus on the Commonwealth. They may see it as old-fashioned, out of date, and a relic of imperialism. These labels risk missing the mark just as calling the EU “A Relic of the Roman Empire”; incorrect and often misleading.

It is true that the UK may possibly not loose economically by not striving for better Commonwealth relations. However, that would be unwise; the UK should not be aiming for the least required in the world to maintain our standard of living. Its aim should be to grow, and eagerly seize opportunities, markets and the ability to network with firm allies and similar nations all over the world. The Commonwealth presents a unique opportunity, and it would be not advisable.

In the network centric 21st Century where resources are already being challenged, it would be unwise to continue blindly with the current allies only. The world is changing; the 21st Century will see the geopolitical power base shift away from the North Atlantic nations towards Asia. As an island nation, the UK cannot risk watching new trade routes opening up by chance without a plan and firm collection of allies and like minded nations around the world. It is not merely the UK that would benefit from closer Commonwealth relations the inverse is very true; this is a key fact that must be kept in mind. This was one of the reasons for the Gambia’s application for re-entry into the Commonwealth.

The Commonwealth is not a Neo-Imperial institution; it is a forum of equals. The very name of the main journal recording Commonwealth issues, first founded in 1910, is called the ‘Round Table’. It is imperative to keep in mind this concept – the Commonwealth is to be as a Chivalric Order composed of equal knights of various strengths of and abilities all of whom work together to seek peace and the general welfare for all.

Groundwork for Going Forward & Proposals:

Therefore, as mentioned above, the qualities of the Round Table are those of the Commonwealth, and for this reason, any new agreement must augment and not replace the Commonwealth of Nations, which is already a great success.

Table of Contents:

The Commonwealth: Past Present & Future

Pt 1: The Commonwealth of Nations

1. Introduction

2. History to Date

A. Up to London Convention

B. Following London Convention

3. Global Role & Work

4. Issues facing the CW – Continuing Relevance & The Future

5. Why closer relations & Freer Trade?

Pt 2: Closer Ties

6. Inter-CW Proposals – Historical & Existing

7. Inter-CW Proposals – CANZUK

8. Inter-CW Proposals – The ‘C9′ & Similar Ideas

9. Inter-CW Proposals – Commonwealth Realms & Federation

10. Inter-CW Proposals – Defence & ‘TrAID’

11. Proposals – The Commonwealth & The Anglosphere

12. Proposals – The Commonwealth & The World

13. Conclusion: Suggestions & Final Comments

Appendix A: Statistics

Daily Globe British Values, Global Perspective

Daily Globe British Values, Global Perspective